unlikeable female characters and the monstrous-feminine

an analysis of female representation in horror and media

in 1993, barbara creed released her book, “the monstrous-feminine,” in which she argues that female monsters represent deeper cultural fears about women, specifically their bodies and sexuality. creed also analyzes existing examples of the monstrous-feminine: the vampire, the witch, the possessed woman, the monstrous womb, the castrator, and the archaic mother.

looking back to the 1930’s, the monstrous-feminine frequently emerged in supernatural and science fiction narratives. for example, elsa lanchester in “the bride of frankenstein” in 1935. these early portrayals introduced the monstrous-feminine in connection with dangerous, seductive creatures that have unnatural physical transformations.

however, as women stepped into more powerful roles during the 1940’s, female monsters gained depth by exploring deeper societal and psychological struggles, mirroring the discomfort and growing pains of a society in transition. these monsters are a response to a larger social order forced upon women: motherhood, birth, and marriage.

in addition to these topics, the monstrous-feminine is often an expression of abject aspects of the female experience that are considered “impure” or “inappropriate,” as follows:

desire: pleasure, devouring

rage: unhinged, self-inflicted violence, embodiment of trauma and want

hunger: physical, visceral, bodily

ugliness: “deformity,” non-normativity, anti-beauty, repulsiveness

body: literal and political, locatable and metaphorical, body-horror, blood and bodily fluids

a recent example is nightbitch by rachel yoder: a novel/film that portrays a woman who believes she is turning into a dog as she grapples with the transformative (and often isolating) challenges of motherhood. but one of the most familiar (and iconic) examples is carrie white in “carrie” (1976) in which a new kind of monster is created: a teenage girl, transformed by emotional repression and the pressures of girlhood. the infamous prom scene became a prime example of female rage.

previously, female characters were strictly one-dimensional, meant to assist in the development of the male protagonist. they were the mothers, damsels, love interests, etc., existing to serve as symbols by nurturing or challenging the main character. these characters were designed to appeal to the male gaze; women are highly sexualized, weak, submissive, damsel-like, and in need of saving. the bad girls will die, while only the virginal and pure will survive, reinforcing the idea that non-conforming women deserve death and torment.

how can something that portrays women in an undesirable way become a form of empowerment? well, allowing women to serve as characters with depth and showcase their true emotions in an “unladylike” manner is liberating.

as anna bogutskaya argues in her “unlikeable female characters” book, how harshly we judge these unlikeable characters shows us what we’re willing to embrace in women. they show us that two things can be true at once: “we can embody contradictions and be multifaceted; feminism can be embodied in both embracing and rejecting our desires; we can do things that aren’t feminist and still be good feminists.”

the connection between horror and girlhood has created a larger movement in film where women are finally the protagonists. powerful, unapologetic women covered in blood (that isn’t their own) has become its own special genre, making the audience go “good for her!” each time.

women are now at the forefront of horror, and the main enjoyers. this genre has become a safe space for women to celebrate and express their hidden desires and monstrosity. but the sudden rise of women in horror has brought up many questions about the meaning of it all.

some believe that women are now the central focus because we need someone to fear for, and since women are seen as lesser and more fragile, they make for the perfect victims. it’s also known that horror and filmmakers generally enjoy punishing women for the sake of “art.” did you know that a study found that it takes women twice as long to be killed on screen? and to top it off, their deaths are much more explicit and tragic, with overly dramatic high-pitched screams and claws of desperation.

however, the idea of the “final girl” could be a response to this phenomenon. as you may know, the “final girl” is a trope found in horror movies, particularly slasher films, where a female character is the “last one left alive to confront the killer. she is the sole survivor who is left to tell the story; often depicted by a seemingly ordinary person who displays unexpected resilience and strength to overcome the threat.”

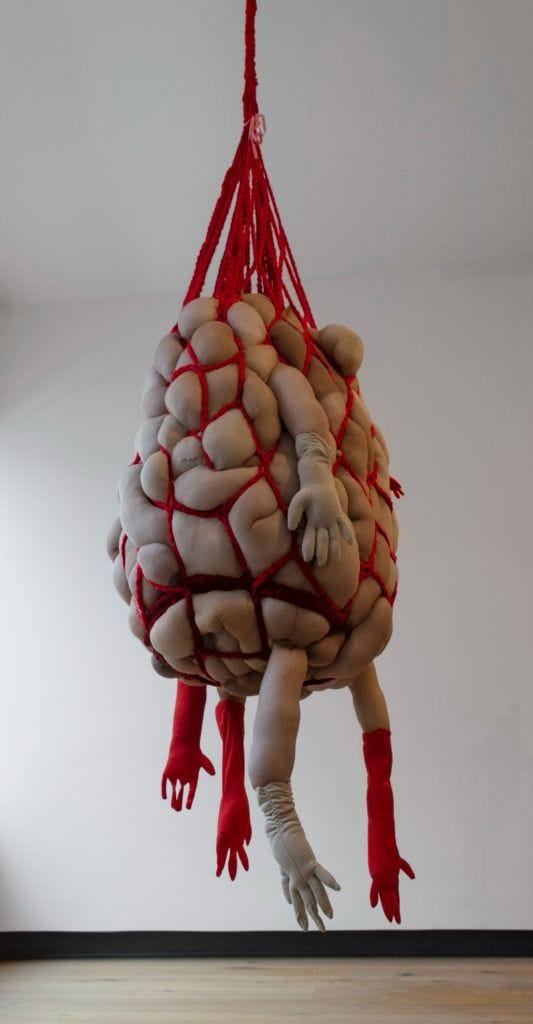

the monstrous-feminine has found its place in all forms of art, not just film. for example, the “grotesque-feminine,” commonly in relation to art, examines the dark, ugly side of the female experience. the feminine grotesque brings forth the impossible criteria that we have placed on women’s bodies.

the art itself is distorted and dystopian — featuring slabs of meat, dismembered organs, makeup, and glitter, with both fantasical and human elements. it explores the concept of “ugliness” in relation to the freedom that it provides from the hungry eyes of men. personally, i find this art beautiful and powerful, when done correctly. i wouldn’t say that using fat or disabled bodies could classify as “grotesque art,” because it implies that there is something disturbing about their existence, which goes against the point that the art is looking to make.

back to films — “the substance” has been a fan-favorite this year, and i find that it’s a perfect mix of all of these elements: the monstrous-feminine, grotesque art (body horror), and unlikeable female characters. the film been focused on particularly for its satisfying body horror — margaret qualley quite literally comes out of demi moore’s back. it’s disturbing and perfectly grotesque, a combination that you cannot look away from.

another lesser-known (but still known) example is “love lies bleeding,” starring katy o-brian and kristen stewart, where bodybuilder o-brian grows to the size of a giant and crushes the manipulative and powerful men that have been coming after her and her girlfriend. this thriller was equally confusing and symbolic.

as we wrap up the year, it’s the perfect time to reflect on how the monstrous-feminine reveals itself in 2024. the monstrous-feminine, grotesque-feminine, and unlikeable female characters have all come together to create an unforgettable feminist movement within art and film.

SOURCES:

https://www.bfi.org.uk/features/monstrous-feminine-female-monsters

https://www.stylist.co.uk/entertainment/tv/women-in-tv-antiheroine-nice-girl-era/814832

So happy to see The Substance in here. I honestly don’t think enough people saw it, the undertones about aging as a woman are so powerful even though it was a little bit campy and grotesque at times lol

I absolutely LOVE this piece (and women in horror, all of them)